TITLES OF NOBILITY ACT or

THE ORIGINAL 13TH AMENDMENT

Most people do not realize that the well-known thirteenth amendment - that which ended slavery in America - was not the first "Thirteenth" amendment proposed. As any Constitutional scholar (or anyone remotely familiar with American History) can readily tell you, the thirteenth amendment to the United States Constitution is an important one. Perhaps even the mostimportant one of all. As most students learned at some point in school but quickly forgot, the thirteenth amendment that is so well known today was ratified by congress in 1865, and effectively abolished slavery in the United States.

While this amendment didn't exactly end racism once and for all (it’s proven rather difficult to make laws to that effect), it certainly was quite an important step in that direction.

But the true history of the thirteenth amendment actually goes back much farther than The Civil War, and has very little to do with slavery.

The story begins in 1810, fifty-five years before slavery would be abolished.

There was a young woman from Baltimore, Ms. Betsy Patterson. This young lady, in some kind of flight of youthful fancy, moved to England, where she married Napoleon Bonaparte's younger brother, Jerome, and with him had a child, young Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte (the young couple were clearly not known for coming up with clever names). Now, because of his mother's heritage, this child by law was granted automatic citizenship into the United States, while at the same time retaining a status of nobility in France, being Napoleon's nephew and all.

There were many among the nobles in America who viewed this as a travesty to their own national identity, and quite a good reason to add a little something to the Constitution that was apparently missing.

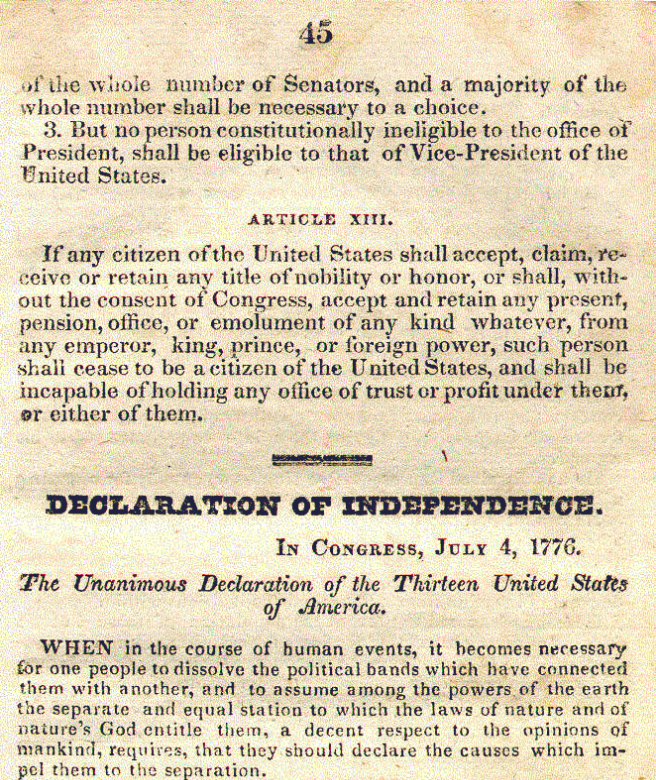

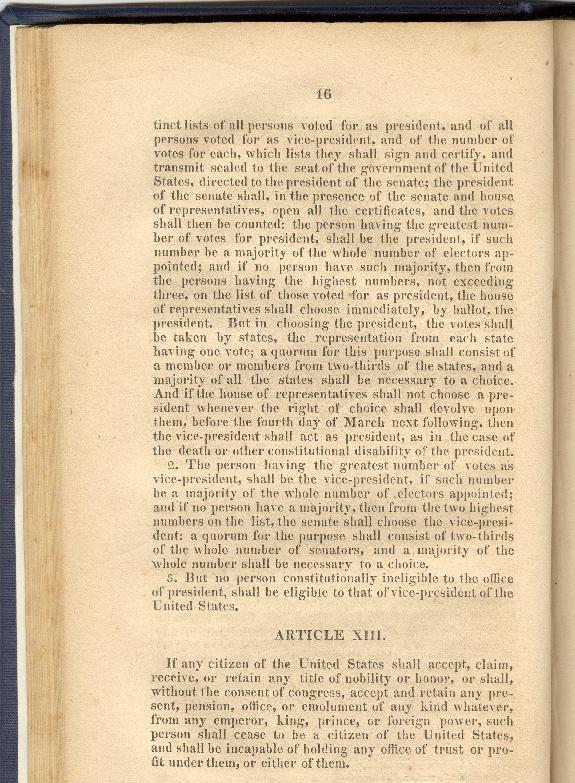

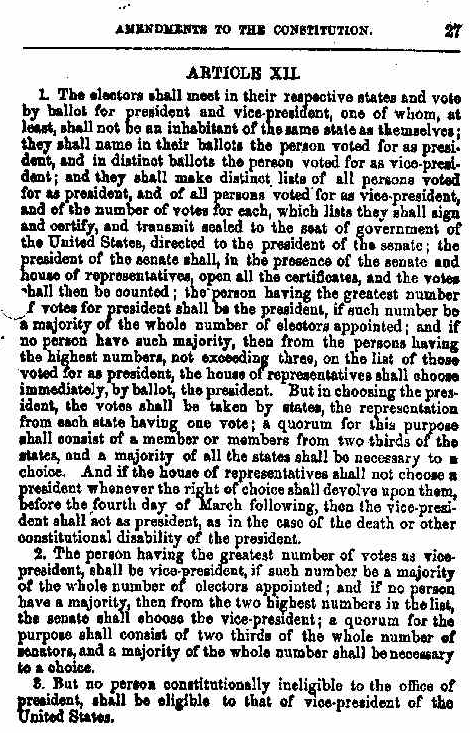

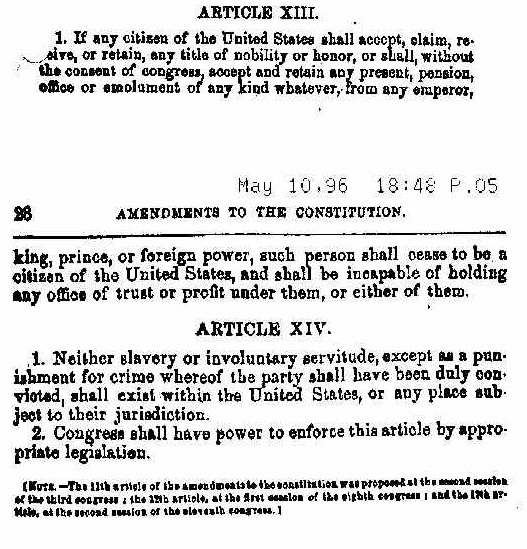

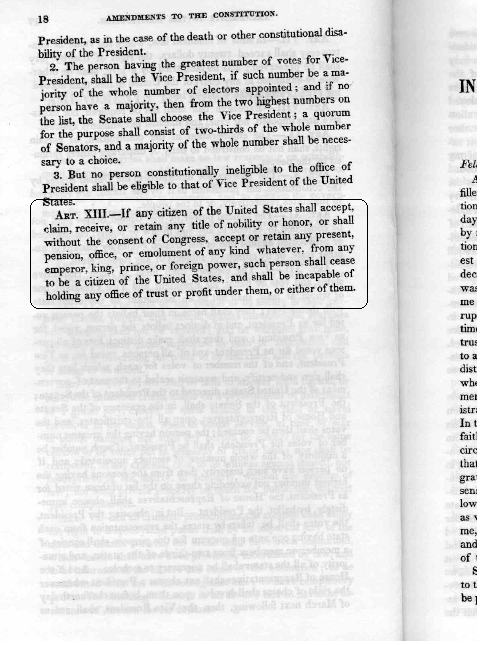

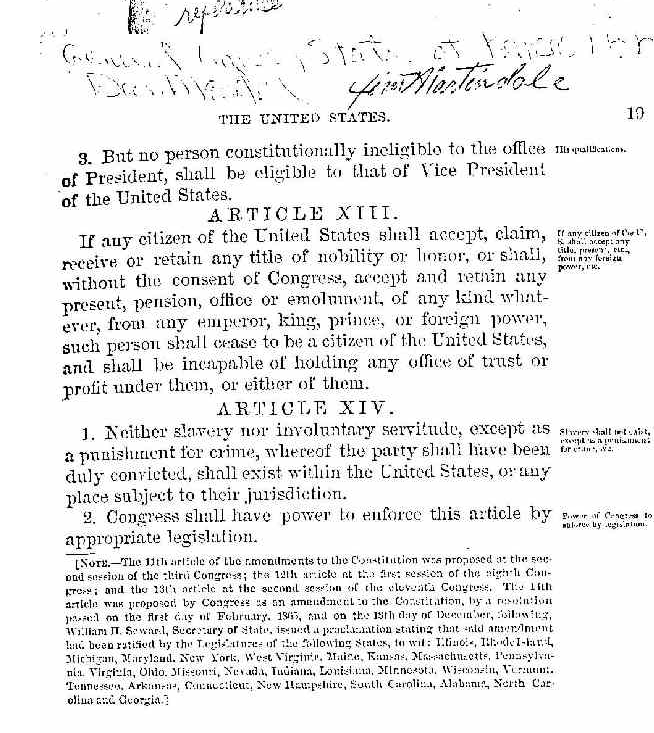

And thus was born the Titles of Nobility Act; a proposed constitutional amendment (it would be, of course, the 13th) stating that any citizen of the U.S. who receives a title of nobility or honor from a foreign nation without the consent of congress must be forced to give up his or her citizenship in the United States.

Apparently, the proposed amendment must have sounded quite good to congress at the time, as it passed quickly through both houses by quite a wide majority, then was sent down to the individual state legislatures to be voted on (as article 5 of the constitution requires). It is here that the amendment finally found trouble.

Such an amendment would have required approval of two thirds of the states for ratification. After three years of debate (as the War of 1812 continued to rage), the amendment finally fell just shy of the required state approval, and thus was not added to the constitution.

Or was it?

The Short, But Interesting, Legacy For several decades, it was quite a common misconception among many Americans that the Titles of Nobility Act had, in fact, been approved. Much of this can probably be blamed, one must suppose, on the yet-primitive methods of communication available in the nineteenth century. In fact, communication over long distances hadn’t been much improved over the previous several centuries at this point, apart from the introduction of the steam engine, which hadn’t yet caught on at this point, having been invented only a few years previously.

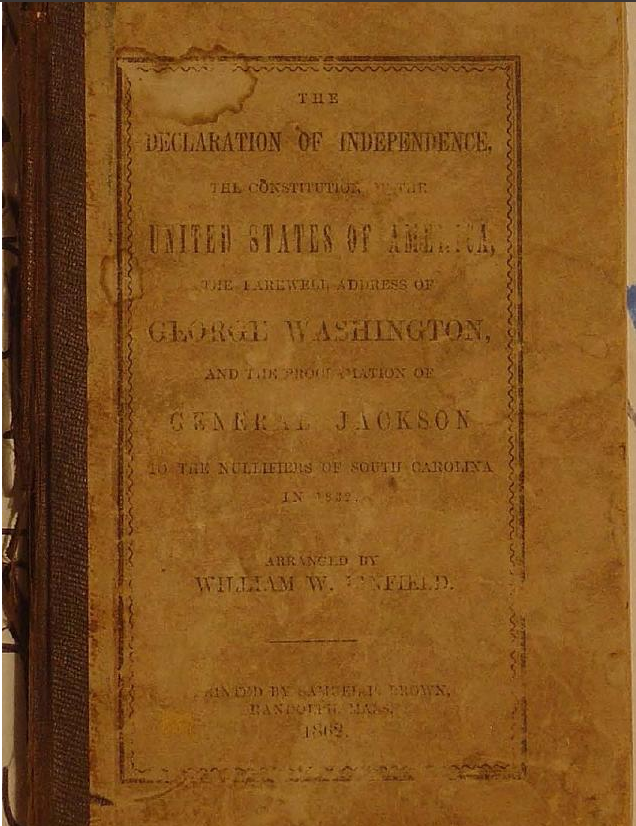

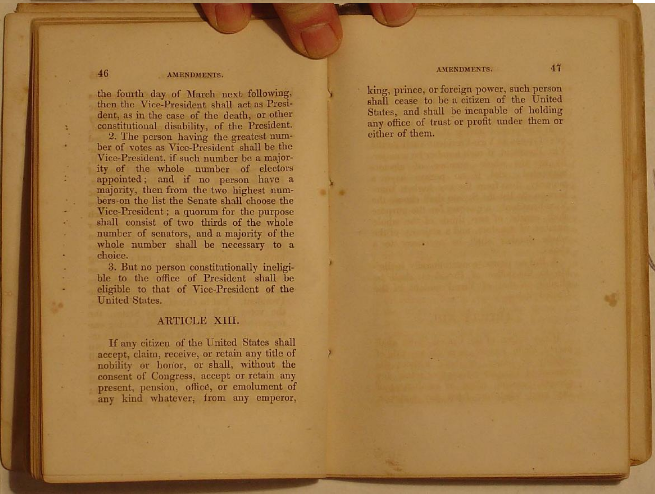

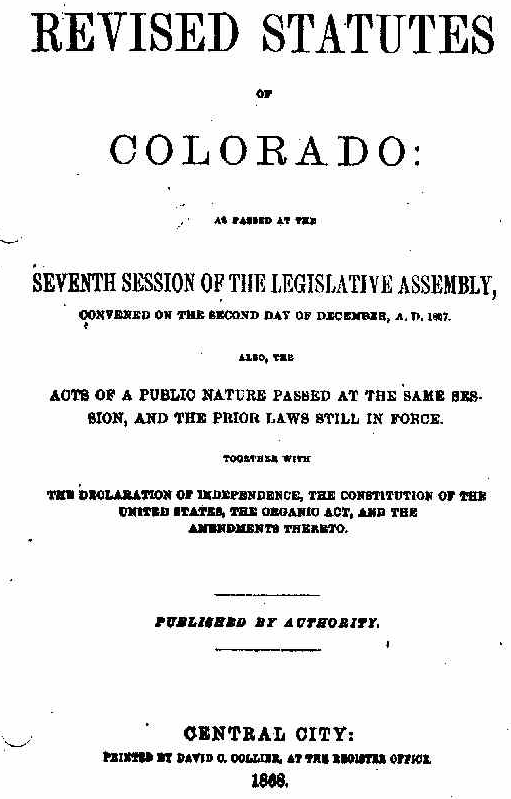

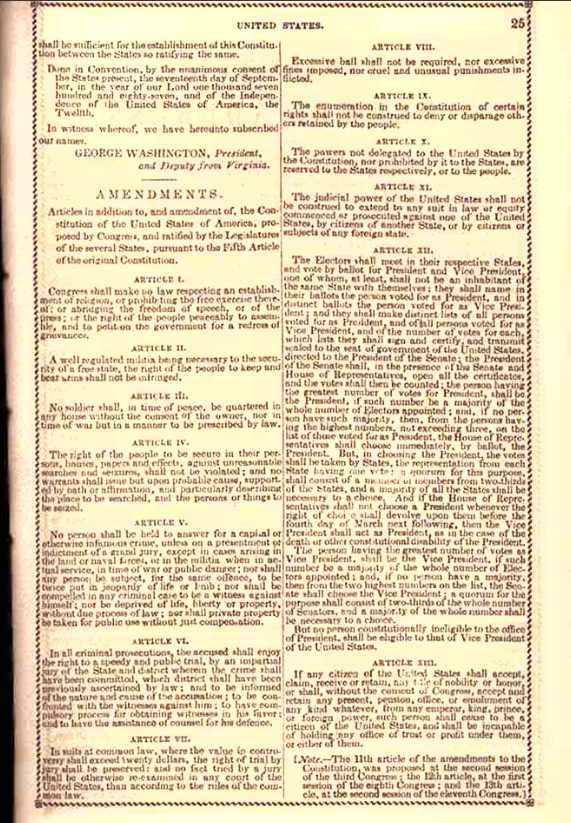

Similarly, the telegraph wouldn’t come for a few more decades, then the phone a few decades after that. In fact, word that the Titles of Nobility Act had failed spread so poorly that the amendment was actually included in several printings of the constitution during this time before the folks at the printing presses themselves finally got a clue. Eventually, it seems that people began to realize the error of their ways, though it wouldn't surprise me if more than a few people were a bit confused when congress took it upon themselves to issue another thirteenth amendment forty years later.

Of course, this is not the end of the story. Even today, there is absolutely no end of websites and message boards (including the "Titles of Nobility Act Research Committee") who declare the Titles of Nobility Act to have been passed in truth, but then swept under the rug by a vast government conspiracy. It's an interesting thought, to be sure, but constitutional scholars tend to agree that the amendment did not, in fact, pass. If they somehow could have conspired to remove the act from the constitution, however, this surely deserves some sort of praise, as such a thing must not have been easy.

In closing, here are just a few of the many people who should lose their citizenship:

While this amendment didn't exactly end racism once and for all (it’s proven rather difficult to make laws to that effect), it certainly was quite an important step in that direction.

But the true history of the thirteenth amendment actually goes back much farther than The Civil War, and has very little to do with slavery.

The story begins in 1810, fifty-five years before slavery would be abolished.

There was a young woman from Baltimore, Ms. Betsy Patterson. This young lady, in some kind of flight of youthful fancy, moved to England, where she married Napoleon Bonaparte's younger brother, Jerome, and with him had a child, young Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte (the young couple were clearly not known for coming up with clever names). Now, because of his mother's heritage, this child by law was granted automatic citizenship into the United States, while at the same time retaining a status of nobility in France, being Napoleon's nephew and all.

There were many among the nobles in America who viewed this as a travesty to their own national identity, and quite a good reason to add a little something to the Constitution that was apparently missing.

And thus was born the Titles of Nobility Act; a proposed constitutional amendment (it would be, of course, the 13th) stating that any citizen of the U.S. who receives a title of nobility or honor from a foreign nation without the consent of congress must be forced to give up his or her citizenship in the United States.

Apparently, the proposed amendment must have sounded quite good to congress at the time, as it passed quickly through both houses by quite a wide majority, then was sent down to the individual state legislatures to be voted on (as article 5 of the constitution requires). It is here that the amendment finally found trouble.

Such an amendment would have required approval of two thirds of the states for ratification. After three years of debate (as the War of 1812 continued to rage), the amendment finally fell just shy of the required state approval, and thus was not added to the constitution.

Or was it?

The Short, But Interesting, Legacy For several decades, it was quite a common misconception among many Americans that the Titles of Nobility Act had, in fact, been approved. Much of this can probably be blamed, one must suppose, on the yet-primitive methods of communication available in the nineteenth century. In fact, communication over long distances hadn’t been much improved over the previous several centuries at this point, apart from the introduction of the steam engine, which hadn’t yet caught on at this point, having been invented only a few years previously.

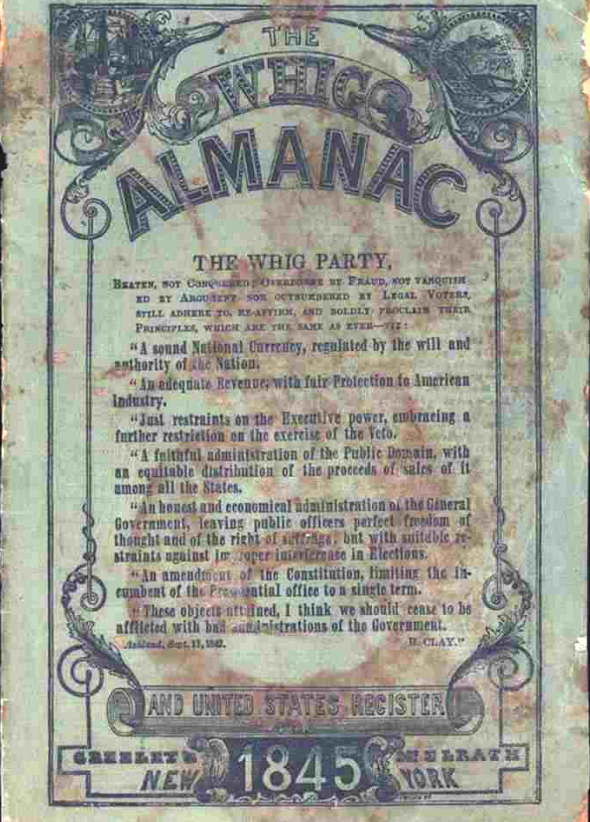

Similarly, the telegraph wouldn’t come for a few more decades, then the phone a few decades after that. In fact, word that the Titles of Nobility Act had failed spread so poorly that the amendment was actually included in several printings of the constitution during this time before the folks at the printing presses themselves finally got a clue. Eventually, it seems that people began to realize the error of their ways, though it wouldn't surprise me if more than a few people were a bit confused when congress took it upon themselves to issue another thirteenth amendment forty years later.

Of course, this is not the end of the story. Even today, there is absolutely no end of websites and message boards (including the "Titles of Nobility Act Research Committee") who declare the Titles of Nobility Act to have been passed in truth, but then swept under the rug by a vast government conspiracy. It's an interesting thought, to be sure, but constitutional scholars tend to agree that the amendment did not, in fact, pass. If they somehow could have conspired to remove the act from the constitution, however, this surely deserves some sort of praise, as such a thing must not have been easy.

In closing, here are just a few of the many people who should lose their citizenship:

- Wesley Clark, U.S. General and NATO Supreme Allied Commander in Europe made Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire March 28, 2000

- Norman Schwarzkopf and Colin Powell, U.S. Military Generals, appointed in 1993 as Knights Commander of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath (Honorary) by H.M. Queen Elizabeth

- George H.W. Bush, former U.S. President, appointed Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, 1993, by H.M. Queen Elizabeth

- Ronald Reagan, former U.S. President, appointed Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, 1989, by H.M. Queen Elizabeth

- Caspar Weinberger, former U.S. Secretary of Defense, appointed Knight Grand Cross of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire by H.M. Queen Elizabeth

- Tom Foley, former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. March 19, 1995. Member, Order of the British Empire. Foly also holds the French Legion of Honor and the German Order of Merit

- Admiral Leighton W Smith Jr., USN, was appointed as an Honorary Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (Military Division) (KBE) 1997 by Queen Elizabeth II .

- Alan Greenspan, former Federal Reserve Chairman, 2002 by Queen Elizabeth II

- Rudy Giuliani, former Governor New York City, appointed Knight Commander of the Most

Excellent Order of the British Empire, 2002, by Queen Elizabeth II

SO TO WHICH DO THESE MEN OWE THEIR ALLEGIANCE? WE HAVE

LEARNED YOU CANNOT SERVE TWO MASTERS

No man can serve two masters: for either he. will hate the one, and love the other; or else. he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon. Matthew 6:24 KJV

Now to understand the importance of this - the reason a lawyer would have been prohibited from holding office is because the International Bar Association was charted by the King of England and headquartered in London. So any American lawyer who used or uses the term Esquire would be in violation of the Constitution, Article 1, Sect. 9:

No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of Congress, accept of any present, Emolument (a salary, fee, or profit from employment or office; salary, pay, wage(s), earnings, allowance, stipend, honorarium, reward or premium), Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince or foreign State.

But since there was no penalty for this, it was largely ignored. This would also be pretty defunct today, as most of our lawyers belong to the ABA, or American Bar Association, so only fools who belong to the IBA would fall under this domain. So basically, unless you accept a foreign title, say Knight, you will not be affected and forced to forfeit your citizenship.

This makes the Original 13th Amendment a very important document and the very fact it was removed and replaced by the current 13th Amendment after the end of the Civil War implies just who was responsible for this act. Does your lawyer refer to himself or herself as ESQUIRE?

Too bad those who were involved in this fraud have been dead for over 150 years because I for one would like to have heard the excuses they would have used since by creating and carrying out this fraud showed what kind of men they were, Probably the very same ones who were entangled in taking away our status as a Republic and making the country and all the states, counties, cities and towns in this country a corporation. And they wonder why we don't trust them!

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| original_13th_amendment.pdf | |

| File Size: | 2184 kb |

| File Type: | |

The Mystery of the 13th Amendment

The American Revolution has just concluded and England has realized that they could not squash the young republic with military might. So they went to the usual bag of tricks for politicians. Though titles of nobility were prohibited by both Article VI of the Articles of Confederation (1777) and in Article I, Sect. 9 of the Constitution of the United States (1778), the Founding Fathers saw a considerable loophole. A loophole that today has given us Sir Rudy Giuliani, Sir Colin Powell and Sir Ronald Reagan.

In the winter of 1983, archival research expert David Dodge, and former Baltimore police investigator Tom Dunn, were searching for evidence of government corruption in public records stored in the Belfast Library on the coast of Belfast, Maine. By chance, they discovered the library's oldest authentic copy of the Constitution of the United States which was printed in 1825. Both men were stunned to see this document included a 13th Amendment that no longer appears on current copies of the Constitution. Moreover, after studying the Amendment's language and historical context, they realized the principle intent of this "missing" 13th Amendment was to prohibit lawyers from serving in government.

So began a seven-year, nationwide search for the truth surrounding the most bizarre Constitutional puzzle in American history -- the unlawful removal of a ratified Amendment from the Constitution of the United States. Since 1983, Dodge and Dunn have uncovered additional copies of the Constitution with the "missing" 13th Amendment printed in at least eighteen separate publications by ten different states and territories over four decades from 1822 to 1860. (Below is the letter of certification from the Texas State Library that they hold a copy of the Virginia State Constitution of which had edited their Constitution to match the addition of the original 13th amendment.)

In June, 2007, Dodge uncovered the evidence that this missing 13th Amendment had indeed been lawfully ratified by the state of Virginia and was therefore an authentic Amendment to the American Constitution. If the evidence is correct and no logical errors have been made, a 13th Amendment restricting lawyers from serving in government was ratified in 1819 and removed from our Constitution during the tumult of the Civil War.

Since the Amendment was never lawfully repealed, it is still the Law today. The implications are enormous.

In the winter of 1983, archival research expert David Dodge, and former Baltimore police investigator Tom Dunn, were searching for evidence of government corruption in public records stored in the Belfast Library on the coast of Belfast, Maine. By chance, they discovered the library's oldest authentic copy of the Constitution of the United States which was printed in 1825. Both men were stunned to see this document included a 13th Amendment that no longer appears on current copies of the Constitution. Moreover, after studying the Amendment's language and historical context, they realized the principle intent of this "missing" 13th Amendment was to prohibit lawyers from serving in government.

So began a seven-year, nationwide search for the truth surrounding the most bizarre Constitutional puzzle in American history -- the unlawful removal of a ratified Amendment from the Constitution of the United States. Since 1983, Dodge and Dunn have uncovered additional copies of the Constitution with the "missing" 13th Amendment printed in at least eighteen separate publications by ten different states and territories over four decades from 1822 to 1860. (Below is the letter of certification from the Texas State Library that they hold a copy of the Virginia State Constitution of which had edited their Constitution to match the addition of the original 13th amendment.)

In June, 2007, Dodge uncovered the evidence that this missing 13th Amendment had indeed been lawfully ratified by the state of Virginia and was therefore an authentic Amendment to the American Constitution. If the evidence is correct and no logical errors have been made, a 13th Amendment restricting lawyers from serving in government was ratified in 1819 and removed from our Constitution during the tumult of the Civil War.

Since the Amendment was never lawfully repealed, it is still the Law today. The implications are enormous.

You may verify the Maine document by contacting:

Maine State Archives

State Capitol - Station 84

Augusta, ME 04333-0084

(207)287-5295

[email protected]

Maine State Archives

State Capitol - Station 84

Augusta, ME 04333-0084

(207)287-5295

[email protected]

MILITARY LAWS of the UNITED STATES 1825

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| 1819_united_states_constitution_attested_a.pdf | |

| File Size: | 2523 kb |

| File Type: | |